Featured in this issue:

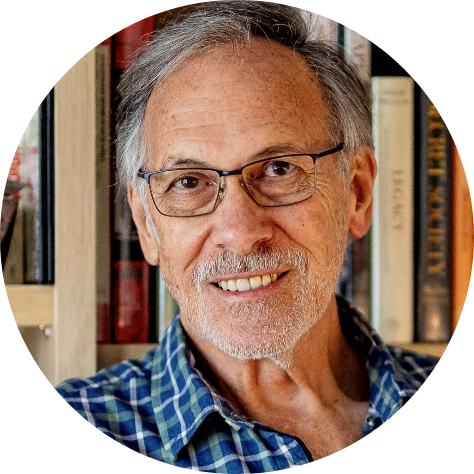

From the Chairperson’s Desk: Willem Landman

The Exit Interview: Sean O’Connor

Expert Input: How Laws are Made - and Where We Can Intervene

Popcorn Time: “Bugonia,” a film by Yorgos Lanthimos

Good Reads: Women Who Run with the Wolves: Clarissa Pinkola Estés

Poetry Apothecary: “The True Love” - David Whyte

From the Chairperson’s Desk

Taking Stock: Of what our court challenge entails, but also of significant moments in DignitySA’s journey that brought us to this point

In early 2026, DignitySA will approach the North Gauteng High Court in Pretoria to set in motion a process to decriminalise and legalise assisted dying in South Africa.

“Assisted dying” means a medically assisted death that is either self-administered or doctor-administered, with strict eligibility criteria and effective safeguards in place.

This assisted dying court application – this constitutional challenge – is an appropriate time to take stock not only of what this court challenge entails, but also of significant moments in DignitySA’s journey that brought us to this point.

DignitySA’s constitutional challenge is the culmination of 15 years of work towards explicit legal recognition of the right of South Africans to choose assisted dying when their life trajectory places them in a position where available, legal options fail to mitigate – even compound – their intractable and unbearable suffering.

DignitySA has its origins in a chance meeting between Sean Davison and me in a television studio in Johannesburg, where we were participants in a panel discussion about “euthanasia”. We discovered that we shared the same commitment to human dignity, freedom of choice, and justice for individuals whose suffering has become all-consuming and for whom death has become the relief of choice.

We were convinced that our Constitution looks compassionately, but also as a matter of right, upon those who die terrible deaths while our legal tradition fails to do so. In effect, our common law considers assistance with dying as no different from killing in cold blood. That is unconscionable.

So, we founded DignitySA. Until as recently as late 2022, we operated on a tiny budget, largely funding expenses ourselves. All along, Sean Davison had to contend with legal defenses, first in New Zealand, then in South Africa, and now in the UK.

We soon realised that end-of-life healthcare needs went far beyond assisted dying – to pain management and palliative care, termination of life-sustaining treatment, and advance directives, particularly living wills. It meant that we had to answer many inquiries, advise about freedoms under, and limits of, the law, intercede with medical professionals on behalf of vulnerable patients and uncertain families, and the like.

Apart from such routine work, over the years there have been several milestones:

In 2015, DignitySA assisted Robert Stransham-Ford to obtain legal counsel for his successful court application to allow him to be legally assisted with dying. DignitySA was, however, not a party to the legal proceedings.

The Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) overturned the High Court ruling on appeal in 2016. Although this was seen as a loss for legalised assisted dying at the time, a full bench of the SCA acknowledged DignitySA’s standing and right to act in the public interest, which is exactly what we are doing now with our court challenge.

In 2018, DignitySA hosted the biennial conference of the World Federation of Right to Die Societies in Cape Town.

Also in 2018, we cooperated with parliamentary law writers to draft an advance directives bill, which was gazetted but came to naught following the election of a new parliament and the Covid pandemic. We are currently exploring various options with interest groups to revive this advance directive initiative.

Just over four years ago, in December 2021, I persuaded Dieter Harck, who suffers from motor-neuron disease, to withdraw his and Dr Sue Walter’s court application to seek legalised assisted dying for themselves and in the public interest. After five years, their application was going nowhere. Because of the Covid pandemic, initial legal proceedings were via the internet, and then the judge who heard the evidence died before a presiding judge could hear legal argument.

I believed that Dieter deserved better, sought strategic legal advice, and then put together a pro bono team of attorneys and advocates to prepare a case to bring to the High Court, including two Senior Advocates to appear in court when the time comes.

The legal team advised us to approach the motion court where argument is heard on documentation rather than having individual applicants appearing in court on their own behalf. DignitySA will be the applicant approaching the court for relief.

Since early 2022 and involving hundreds of hours of dedicated and meticulous preparation, the legal team and DignitySA have cooperated closely to put together our constitutional argument for assisted dying in the form of a Founding Affidavit with supporting and confirmatory affidavits.

Evidence in support of our application involves three major components.

First, 11 case studies of deceased individuals who sought, or would have sought, assisted dying before their death, plus Dieter Harck. These case studies make for profoundly moving personal stories of suffering, fear of abandonment by the healthcare system, and a desire to die a peaceful and dignified death surrounded by loved ones, preferably at home.

Second, we secured the assistance of 16 foreign experts in jurisdictions where assisted dying is legal. Their goodwill and the time they invested have been truly remarkable. They are from six countries and spread over four continents. They are the foremost international experts in this field, and, among others, contributed significantly to the successful assisted dying legalisation initiatives in Canada and Australia. They formulated and reformulated their submissions to give the targeted, detailed input required by our legal team.

Third, using these foreign expert reports as points of reference about how assisted dying works in their countries, South African medical professionals argue that we could introduce a system of assisted dying in South Africa capable of being professionally managed and safely administered by our healthcare institutions and individuals.

The outcome – our Founding Affidavit – is a sustained and persuasive constitutional case for decriminalising and legalising assisted dying in South Africa. We believe that embedded in this constitutional argument is an ethical case for assisted dying because the Bill of Rights of our Constitution is an ethical document. We are indeed deeply thankful for the contribution of so many individuals and organisations towards this wonderful document.

Our application will be opposed by the following respondents: the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development, the National Director of Public Prosecutions (NDPP), the Minister of Health, and the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA).

We ask the court for two kinds of relief:

to decriminalise assisted dying by declaring its blanket common-law prohibition unconstitutional and invalid; and

to suspend the determination of invalidity until Parliament, within 24 months, passes a law legalising assisted dying.

Although we are persuaded that our argument is anchored in a faithful interpretation of our constitutional rights, the legal process must still play itself out, and it could mean the losing party appealing to the SCA and thereafter the Constitutional Court (CC).

We have had widespread support for our initiative, most notably from the eight prominent medical professionals who openly supported our cause and application in the South African Medical Journal in 2024. It was the first time since the Barnard brothers in the 1970s that prominent medical professionals were brave enough to go public unambiguously in support of assisted dying. We have deep appreciation for that, because doing so could be perceived as risky for a medical professional.

Likewise, the South African medical professionals who provided affidavits for our court challenge are brave individuals, but we have little doubt that their courage will be rewarded with the development of our common law, confirming the pre-eminence of the Constitution.

Going to court – the High Court, the SCA and CC – requires substantial funding. Pro bono work involves reduced fees, not free legal labour. After all, our court challenge requires hundreds of hours of time-consuming legal work from a team of six or more lawyers.

We have been fortunate to receive funds to enable us to lodge our High Court papers in February. This funding coincided with young and committed individuals joining DignitySA, creatively and energetically increasing our public footprint.

Despite this turning point for DignitySA, a long advocacy and legal journey still lies ahead, especially if there are appeals to the SCA and CC.

We therefore ask you kindly to donate funds to support our legal costs.

If we miss this historic opportunity, any South African who seeks access to assisted dying in tragic circumstances would be denied this choice for decades to come. To get to this point where we are now requires the cooperation of many individuals and organisations to commit their time and energy without financial reward.

Thank you for following and supporting our journey.

Prof Willem Landman, Chairperson, DignitySA

The Exit Interview

Dignity Matters poses some questions to:

Sean O'Connor is a grief support specialist and counsellor, applied theatre practitioner and facilitator working with group and organisational processes, a podcast producer, writer, media mogul, beachcomber, and general layabout.

If calories and indigestion were no object, what culinary indulgence would be your last?

Well it depends what time of day I’d be blowing my gasket. I won’t be eating muesli for supper, know what I mean? My last meal would have a ‘demise of the proteins’ theme, to accompany the death I’ll be hosting. So perhaps a ‘one meal covers all times of day’ precautionary last indulgence might involve a platter of aged Italian hams and salamis and bits of sausage along with a chilled grape, then a bouillabaisse with all the tentacles and pointy bits. I'd be running a parallel meal on the side, just for contrast, a super-greasy New Orleans muffaletta sandwich and a wedge of chicken liver pate and biscuits as an occasional palate-wrecker and culinary reset. The two strands of the meal will then converge with a hunk of pan-seared Cape Salmon with wilted English Spinach and crispy frites, before an elegant little medallion of pepper-crusted fillet steak medium rare, along with a dash of strong mustard and a pan of roast vegetables. After that I’ll be working through an indecent brick of tiramisu and finally some chocolate mousse and cream. Even though I have avoided alcohol for years, I’ll probably indulge in some Haute Cabriere Chardonnay Pinot Noir, but just a few bottles. And then I’ll be dead.

Ideally, how would you like to go?

Perhaps I could die in a jerky 'taking multiple bullets at once' fashion like in a bad Western after successfully assassinating an unpopular despot (take your pick), but I think I'll just go for the 'peacefully at home option.' My family and a few select friends will be around telling filthy jokes, so they'd better start practising, and hopefully I’ll die laughing.

In what publication would your obituary appear, and what would its glorious and slightly exaggerated but still truthful headline be?

Page 6 of the False Bay Echo. “Fish Hoek man leaves body to Science. Science says, ‘Noooo!’”

Imagine your memorial service. What music would be playing? What band or artist would be grateful for the opportunity to perform?

Bob Dylan, blind and deaf and aged 136, will be mumbling songs with his full band, especially a rousing and incoherent version of “Forever Young.” Then Fontaines DC and Getdown Services will take over for the general mayhem. It’s going to be epic. Make friends with me now, is my advice. Or just send a donation.

Burial or cremation? If transport, permissions and expense were no problem - where would you like to be buried, or have your ashes scattered?

Cremation, after the anatomy students at UCT medical school have deciphered my tattoos – I’m going to leave a cryptic crossword for them to solve, on my bum. They might have to lean in quite far to read the fine print. Then the ashes into the stream in Newlands Forest and on Glencairn Beach, please.

If you could choose one object to be buried or cremated with, what would it be and why?

My childhood friend, Teddy, is coming with. We’ve never been apart, and he helps me sleep.

If you were to haunt someone after your demise, where would it be and why?

I'd turn into a creepy hologram you can operate by remote control and visit my lovely girlfriend, but only in a way she’d want, namely, to listen to her A-grade gossip, kiss her neck with my chilly breath which smells faintly minty, and provide an unearthly echo sound effect to her frequent laughter, which will impress her friends no end. I’ll really miss her when I’m gone.

Who is in your will? And is there anything that you are leaving that may cause a fight?

I hope to expire in a state of perfect weightlessness, after evacuating my last meal, obviously (which could take a while), with nothing but a borrowed funerary shroud festooned with the Arsenal F.C. logo. Most of my scant possessions have already be assigned to their future owners. My omelette pan goes to my daughter. My collection of folktales for my friends. The Abdullah Ibrahim records and all others to my eldest son. My youngest son will get my Speedo.

What do you still need to do before you kick the bucket?

I'd really like to play in the veterans mixed doubles final at Wimbledon. And have tea with Catherine Deneuve. And learn French, obviously.

Finally, is there anything you've secretly wondered about death, but been too polite to ask?

Nope. I believe that we were designed to die. I wonder what kind of death I’ll have, and when? There’s no guarantee I’ll be around when the sun comes up. It’s taken me a long time to cherish this short life, a lot angst, but also great lashings of beauty too. I’m incredibly happy. And lucky. Death has given great meaning to my life – as Saul Bellow said, ‘Death is the dark backing a mirror needs if we are to see ourselves.’ I wonder if I'll be scared, if conscious when it happens? Perhaps I'm preparing for that moment right now. What a privilege it will be to die.

Expert Input

How Laws are Made - and Where We Can Intervene

Alison Tilley is an attorney and the coordinator of Judges Matter. Her work focuses on strengthening transparency, privacy, and the rule of law through research, public education, and strategic engagement with courts, Parliament, and oversight bodies.

Otto von Bismarck is commonly quoted as saying, “Laws are like sausages; it is better not to see them being made.”

Uncomfortable as that image is, it contains more truth than we might like. Law-making is rarely neat. Ideas are added and removed, compromises are struck, and sometimes the most important elements never make it into the final text.

That said, there is a proper way to make law in South Africa — even if it is often honoured more in the breach than the observance. For Dignity South Africa, which seeks legislative reform in relation to assisted dying, understanding this process matters. It helps us recognise when change is possible, and where our voices can have the greatest impact.

Usually, the process begins long before a Bill ever reaches Parliament. The first step is deciding on policy. This can happen through a formal process managed by the South African Law Reform Commission (SALRC), which undertakes research, consults widely, and makes recommendations to government. Alternatively, policy can be developed inside a government department itself. SALRC processes are typically thorough and inclusive, but they can take many years. Departments may also publish White Papers to invite public engagement, although in practice this stage is increasingly compressed or bypassed altogether. This early phase is crucial, because it is where the principles of a law are set — often long before draft wording exists.

Once policy is settled, a draft Bill is prepared, usually by legal drafters within the relevant department. Next, the department submits the Bill to State Law Advisers, who must certify that the Bill is constitutionally compliant. The responsible Minister then proposes the Bill to Cabinet, and before it can be introduced in Parliament, it must be approved by Cabinet. There is an option that allows members of parliament to table private members’ bills. There have been 6 of those in the last 30 years, and they generally don’t have political support across the board.

The Bill is then tabled in Parliament. This simply means it is formally placed before Parliament for consideration. It does not mean that it has been debated or agreed to. The Bill is introduced in the National Assembly, where political parties outline their initial positions.

After this, the Bill is referred to a parliamentary committee. This is where the real work of Parliament happens. The committee examines the Bill in detail, amendments can be proposed, and public submissions or hearings may be held. These proceedings are recorded and published at pmg.org.za, making it possible to follow how a Bill evolves. For civil society organisations, this stage is often the most important opportunity to influence the substance of the law. This is a very intensive phase, with a lot of time needed in Parliament, constantly talking to law makers on what they are proposing. This is where legislative “sausages” can go badly wrong, or be very much improved.

Once the committee finalises the Bill, it returns to the National Assembly for debate and a vote. When it passes, it is sent to the National Council of Provinces, particularly if the Bill affects provincial interests. When both houses agree, the President signs the Bill into law. It is then published as an Act of Parliament and comes into force, either immediately or on a specified later date.

How long this takes can vary enormously. The Cybercrimes and Cybersecurity Bill, for example, was introduced in 2017 without a SALRC process or a formal policy paper. After sustained criticism from civil society, journalists, lawyers, and technical experts, it underwent extensive redrafting and was eventually passed in 2020 as the Cybercrimes Act. Political urgency — reinforced by presidential commitments — played a significant role in accelerating that process. By contrast, the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) followed a much longer path. The SALRC process alone took around seven years. The Bill was introduced in Parliament in 2009 and only passed in 2013, with full implementation coming much later. That delay reflected the constitutional sensitivity and complexity of the issues involved.

There is, however, another route to legal change: constitutional litigation. When the Constitutional Court finds that a law is unconstitutional, it may declare it invalid immediately, or declare it invalid but suspend the order for a period to give Parliament time to fix the defect. The Court does not “send” a Bill to Parliament. Instead, its judgment binds Parliament, often with a clear deadline. Parliament must then identify the constitutional problem, decide how to cure it, and pass corrective legislation within the time allowed. If it fails to do so, the invalidity automatically takes effect, and the offending provisions fall away. This is then a two to three-year process.

For Dignity South Africa, the lesson is a simple but important one. Law reform is not a single moment; it is a process with pressure points. Knowing where a proposal sits and which stage it has reached tells us whether influence is still possible, what kind of advocacy is most effective, and how long change may realistically take.

Seeing how the sausage is made may not be pleasant. But it is often the only way to change the recipe.

Popcorn Time

REVIEW: Bugonia

Reviewed by: Dawid van der Merwe

Rating: ★★★★★

Bugonia: A Delirious Farce About Power, Paranoia, and the Fragility of Human Dignity

Yorgos Lanthimos’s Bugonia arrives like a prank played by a very serious mind. Loosely adapted from the South Korean cult film Save the Green Planet!, it is, on the surface, a madcap kidnapping comedy: two men abduct the CEO of a pharmaceutical conglomerate, convinced she is an alien bent on destroying the Earth. But as with all Lanthimos films, the premise is merely the trapdoor. What follows is a clinical, unsettling, often mordantly funny inquiry into power, belief, and the human need to impose meaning on a world that increasingly resists it.

The film stars Emma Stone, by now Lanthimos’s most fluent collaborator, as the abducted executive, a woman whose icy composure and carefully rationed empathy make her either monstrously inhuman or simply very good at late-stage capitalism. Her captors, played with a brittle intensity by Jesse Plemons and Aidan Delbis, are men unmoored: wounded by personal failures, political impotence, and a culture that speaks endlessly of “agency” while offering very little of it. Their conspiracy theory, that global suffering is the work of literal extraterrestrials, feels less like delusion than a grotesque simplification of truths too large to bear.

Lanthimos stages their encounters in his signature register: deadpan dialogue, ritualistic cruelty, and an aesthetic that renders even domestic spaces faintly totalitarian. The humor lands not as punchlines but as aftershocks. You laugh, and then wonder what exactly you have laughed at. Is it madness, or the desperate logic of people trying to reclaim a sense of control in a world governed by remote systems and unaccountable power?

What makes Bugonia particularly resonant now is its fixation on dignity, who has it, who loses it, and who is allowed to define it. The kidnapped CEO retains her poise even under threat, while her captors oscillate between grandiosity and abasement. The film quietly asks whether dignity lies in rationality, autonomy, or simply the ability to tell a convincing story about oneself. In a society that medicalizes suffering and monetizes survival, paranoia may be less a pathology than a protest.

There is, beneath the absurdity, a moral seriousness that aligns Bugonia with Lanthimos’s best work. Like The Lobster and Poor Things, it interrogates the violence embedded in “normal” systems, corporate, scientific, and therapeutic, without offering the comfort of clear villains or heroes. Everyone here is compromised; everyone is, in some sense, captive.

For viewers attuned to questions of bodily autonomy, end-of-life agency, and the quiet humiliations imposed by institutional power, Bugonia will feel uncomfortably familiar. Its madness mirrors our own cultural moment, in which trust has eroded and extreme narratives rush in to fill the void. The film does not argue for belief in conspiracies, but it does insist on taking the pain that gives rise to them seriously.

Bugonia is not an easy film, nor a reassuring one. It is a jagged, often cruel, sometimes brilliant reminder that when dignity is stripped away by systems, by corporations, by indifference, people will invent almost anything to get it back.

Good Reads

REVIEW:

“Women Who Run With The Wolves”

by Clarissa Pinkola Estés

Reviewed by: Dawid van der Merwe

Rating: ★★★★½

Women Who Run with the Wolves: Clarissa Pinkola Estés and the Original Wild Remix

When Women Who Run with the Wolves first howled into the world in 1992, it didn’t arrive like a polite self-help book; it kicked down the door. Clarissa Pinkola Estés, a Jungian analyst with the soul of a storyteller and the cadence of a desert shaman, delivered something closer to a concept album than a psychology text: a sprawling, myth-soaked manifesto about reclaiming the “Wild Woman,” that instinctual, creative, feral force women have been trained, sometimes lovingly, often brutally, to forget.

Three decades on, the book still feels less like a relic of second-wave feminism and more like a bootleg recording passed hand to hand, dog-eared and underlined, whispered about in book clubs, therapy rooms, and long, late-night conversations that change the direction of a life.

Estés doesn’t write in neat chapters; she riffs. Drawing on fairy tales, folklore, and myth from across cultures, she dissects stories the way a blues guitarist bends notes, slow, deliberate, emotionally raw. Bluebeard becomes a cautionary tale about predatory relationships. La Loba, the Bone Woman, turns into a resurrection hymn for lost creativity. Each story circles the same truth: when women are cut off from their instincts, something essential dies, and when those instincts are reclaimed, everything changes.

This is not a book for skimming. It demands surrender. Estés repeats herself, wanders, sermonizes, and occasionally sounds like she’s preaching to the converted, but that’s part of the point. Like a great live album, the power isn’t in precision; it’s in accumulation. By the time she’s done, you don’t just understand the Wild Woman archetype, you feel like you’ve met her, maybe even remembered that you are her.

Critics have long dismissed the book as indulgent, woo-woo, or overly mystical. That critique misses the cultural moment that made Women Who Run with the Wolves necessary, and the one that keeps it relevant. In a world that still rewards women for compliance, self-erasure, and emotional labor, Estés’s insistence on rage, intuition, boundaries, and creative fire feels quietly radical. This isn’t empowerment as branding; it’s empowerment as excavation.

Reading the book now, in an era of burnout culture, algorithmic femininity, and commodified “self-care,” Women Who Run with the Wolves lands like a corrective. It doesn’t offer hacks. It doesn’t promise optimisation. It asks for something harder: attention, honesty, and the courage to listen to the part of yourself that knows when it’s time to leave, to fight, to create, or to grieve.

This is a book that won’t change your life in a weekend, but it might stalk you for years, showing up at moments of crisis or transition like a familiar song you didn’t know you needed. It reminds us that beneath the noise, the performance, and the damage, there’s still a pulse. Still a howl.

And once you hear it, it’s very hard to go back to sleep.

South African Update

Securing the "Last Right": A Landmark Challenge for Human Dignity

For 15 years, DignitySA has stood as the only non-profit organisation consistently campaigning for the legalisation of assisted dying in South Africa. We believe every South African deserves a meaningful life and a dignified end.

Following years of meticulous preparation, we will be launching a historic court case in early 2026. Our case is supported by a substantial body of evidence, including 11 case studies and 18 expert reports from South African and international professionals.

While we have secured highly regarded legal counsel and support, many of whom are working pro bono or at discounted rates, the road ahead will be long.

To sustain proceedings in the High Court, we must raise a minimum of R2 million for legal fees in the coming year.

DignitySA regards this as 'the last right' to be secured in a democratic South Africa. To help us you can:

Donate Today: Help us secure the funds needed to see this case to the end. Visit https://www.dignitysouthafrica.org/support#donate

Learn More: Review our 15-year track record and governance reports at dignitysouthafrica.org/our-reports.

Get in Touch: Contact Leigh at leigh@dignitysouthafrica.org to find out more about how you can support our campaign.

Global News Round-Up

In the last two months, there have been significant developments in the global landscape for assisted dying.

On the 20th of January 2026, Jersey became the first part of the British Isles to establish a fully operational assisted dying service, potentially launching in 2027. The new law ensures that the health minister to provide end-of-life care for the last 12 months of citizens lives.

In the United Kingdom, Lord Falconer proposed a special motion this month to allocate more parliamentary time for the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, warning that the current pace of scrutiny threatened to let the Bill "fail through lack of time" before the end of the session. The House continues to sit on Fridays to progress the legislation.

In the United States, major legislative victories were secured with Illinois becoming the 13th U.S. jurisdiction—and the first in the Midwest—to authorise medical aid in dying. New York is set to follow suit following Governor Hochul’s announcement in December that she had reached an agreement with the State Legislature to sign the Medical Aid in Dying Act. In Delaware, the state's assisted dying law, which was signed in 2025, officially went into effect on the 1st of January 2026.

In New Zealand, MP Todd Stephenson has submitted proposals for expanding the 2019 End of Life Choices Bill that would remove the "six-month prognosis" requirement for eligibility, allow medical practitioners to initiate conversations about assisted dying with patients (currently prohibited) and introduce a "waiver of final consent" for patients who lose mental capacity between approval and the date of death.

More articles from our website

Join Us

Become a member of DignitySA by signing up at https://www.dignitysouthafrica.org/sign-up It’s free.

Members receive exclusive access to our resources and extended versions of our podcasts, as well as invitations to events including our online Annual General Meeting. We will also send our newsletter, DignityMatters, straight to you inbox.

For more information and any queries, please contact info@dignitysouthafrica.org

Poetry Apothecary

There is a faith in loving fiercely

the one who is rightfully yours,

especially if you have

waited years and especially

if part of you never believed

you could deserve this

loved and beckoning hand

held out to you this way.

I am thinking of faith now

and the testaments of loneliness

and what we feel we are

worthy of in this world.

Years ago, in the Hebrides

I remember an old man

who walked every morning

on the grey stones

to the shore of the baying seals,

who would press his hat

to his chest in the blustering

salt wind and say his prayer

to the turbulent Jesus

hidden in the water,

and I think of the story

of the storm and everyone

waking and seeing

the distant

yet familiar figure

far across the water

calling to them,

and how we are all

preparing for that

abrupt waking,

and that calling,

and that moment

we have to say yes,

except it will

not come so grandly,

so Biblically,

but more subtly

and intimately in the face

of the one you know

you have to love,

so that when we finally

step out of the boat

toward them, we find

everything holds

us, and confirms

our courage, and if you wanted

to drown you could,

but you don’t

because finally

after all the struggle

and all the years,

you don’t want to any more,

you’ve simply had enough

of drowning

and you want to live and you

want to love and you will

walk across any territory

and any darkness,

however fluid and however

dangerous, to take the

one hand you know

belongs in yours.

'The Truelove' in DAVID WHYTE: ESSENTIALS

© 2020 David Whyte & Many Rivers Press

www.davidwhyte.com